(A look at the situation in Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Botswana)

It was the erstwhile Liberian warlord, Charles Taylor, who proved that a political leader could corner the mineral resources in his country and use them for personal gains. In his case, he went beyond his country and plundered the diamonds in Sierra Leone. Well, those days seem to be gone and Mr. Taylor is serving a 50-year jail term. The point is that African countries have begun all sorts of efforts to tackle corruption, the bane of development in the continent.

Tanzania

In Tanzania, for instance, the police have made great progress in checking the international smuggling of diamonds in the country. Heaps of diamonds worth about 28 million Euros ($33.4 million) were reportedly seized at the country’s main airport. Petra Diamonds, the largest diamond company in the world, based in Jersey, put the volume of the consignment at 14 kilos. But Tanzanian authorities said it weighed a lot more than that, estimating it to be 30 kilos. The rough diamonds, believed to be from Williamson mine, were meant for export to Belgium for processing.

The Williamson mine in the north of Tanzania is a joint venture. 75 percent belongs to Petra Diamonds, 25 percent to the Tanzanian government. Tanzania’s president, John Magufuli, has declared that combating corruption in the mining sector is a priority for his government. His anti-corruption platform played a large part in helping him to power in 2015.

Benedict Mahona, an economics expert from the University of Dar-es-Salam, told reporters that the seizure of the diamonds from the Williamson mine was lawful. He explained that the customs laws of the East African Community are unambiguous: Every product that is imported or exported from the area must be correctly registered and declared. “Globally operating companies are systematically plundering Africa’s diamond resources, and only a fraction of the stones are properly declared and have duty paid on them,” Mahona said. He also commented that the theft of diamonds almost always happens with the help of corrupt local residents.

Some observers feel that the tough approach by the Tanzanian government could make the international companies to withdraw from doing business in the country. When this happens, jobs will be lost, according to Rebekka Rumpel, an expert in natural resources, based in London. “Tanzania’s tough approach is bound to impact negatively on the country’s image,” she says. Rumpel reports that a large-scale investor from Russia who wanted to mine Tanzanian uranium has already put his project on hold, in part because he was worried about the investment climate in Tanzania.

President Magufuli announced that Tanzanians might take over the diamond mines if the foreign companies continued to be a “problem.” Amani Mhinda, an activist with the group, Haki Madini, describes this as “pure populism.” Haki Madini is a non-governmental organization that advocates transparency in business. “That didn’t work in the past, either,” says Mhinda. “Indigenous companies are at least as corrupt as foreign ones.”

Tanzania is more of a mid-level player on the African diamond market. The East African country is ranked tenth among the continent’s biggest diamond producers. The Tanzanian government hopes that by 2025 the mining industry will contribute at least twice as much GDP as it has to date. At the moment its contribution is less than four percent.

(Pix – President John Magufuli)

Zimbabwe

In Zimbabwe, diamonds have not brought prosperity to the country, either. Three quarters of people in Zimbabwe, Africa’s fifth largest diamond producer, live in extreme poverty. The Zimbabwean government does not give out precise information about how much diamonds contribute to its revenue. “Billions have vanished before ever reaching the Zimbabwean Treasury,” the current report by the British anti-corruption group Global Witness states. The diamonds, it says, have not benefited ordinary people. On the contrary: According to this report, the country’s secret service and military have siphoned off a significant portion of the revenue for themselves, and have used it to finance their activities. “Zimbabwe’s democracy has been undermined and it has led to serious human rights abuses,” says Michael Gibb, who submitted the report for Global Witness.

Similar structures to those in Zimbabwe are also to be found in other big diamond countries in Africa. Diamond deposits have also led to more poverty, violence and oppression in Angola or the Democratic Republic of Congo.

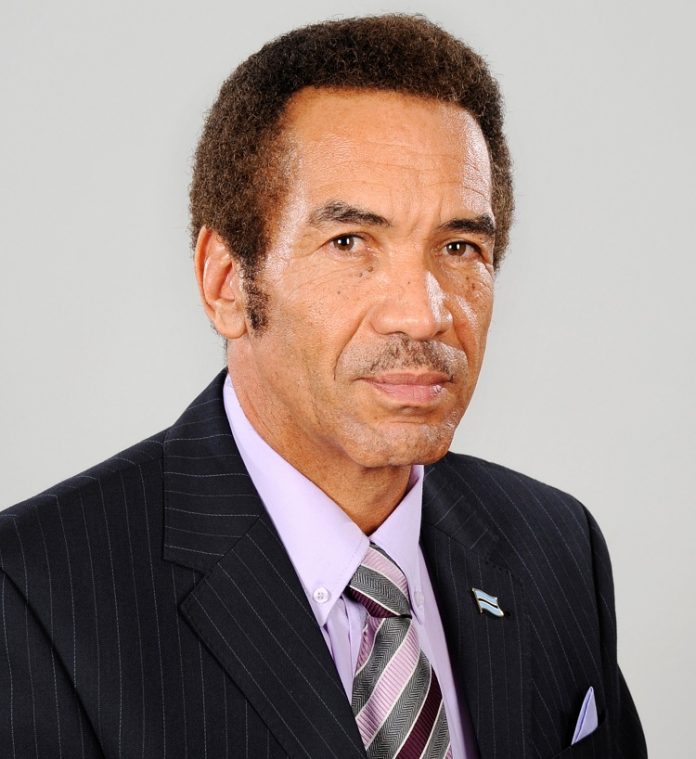

Botswana

Luckily, things are different in Botswana. The biggest diamond producer in Africa is regarded as a model in many respects in terms of channeling profits from the export of raw materials back to the society. 75 percent of the country’s foreign exchange revenue comes from the sale of rough diamonds.

Botswana seems to have learned from the negative examples in Africa. It tries to keep the value added chain in the country for as long as possible. A large quantity of the rough diamonds are processed – divided, cut, polished, drilled – in Botswana itself. Until just a few years ago, this was done in, for example, the Belgian city of Antwerp, or in Israel. This is still the case with other African diamond producers.

Unlike almost all the other countries in Africa, Botswana has handled its riches carefully. The government affords itself social programs that its African neighbors regard with envy. These include free school education and free health care. In addition, part of the money from diamond mining is put towards improving the road, telephone and internet networks.

The government has worked hard not only to protect the industry but also to channel proceeds from there to welfare packages that benefit every citizen. Close watchers of the country’s economy believe that what Botswana needs to do now is to aggressively invest profits from diamond mining in building up other branches of industry as well. They say this is a sure way to guarantee that the bulk of the country’s wealth will keep circulating within the polity.