Analysis by Pat Chukwuelue

The school of thought which argues that it is better to jaw-jaw than to war-war has a point, which governments tend to ignore. The federal government of Nigeria now shudders at the thought of discussing a peace deal with militant and rebel groups in the country in order to bring an end to both the hay wire politics and the high level of violence plaguing the country for some time now. But some governments in Africa have begun to see the need to parley with all separatist and disgruntled groups in order to come up with sustainable agreements that address the notion of peace and social justice.

Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa, has been known to hold rallies, meetings and conferences, where specific plans for peace and progress have been discussed in the past months and years, yet instability continues in parts of the republic. But Nigeria is not really alone in this dilemma. The situation is the same in many African countries, especially those practicing representative democracy and those facing the cycle of elections. In Kenya, Congo DR and Central African Republic, to mention a few, there is no love lost between citizens and their central governments.

But are the terms, peace and social justice mutually exclusive? The problem is that governments preach the need for national peace and security but are hesitant to entrench social justice and fairness. Some people in Africa insist that there will be no peace until the rivers of justice begin to flow in the land. In Nigeria, for example, it was the religious group, the Catholic Bishops Conference of Nigeria, CBCN, which set the ball rolling. Rising from its 2017 forum in Abuja, the group urged the political authorities to take urgent steps to reach out to leaders of all aggrieved groups in the country and see how to meet their demands. But the politicians and technocrats in the commanding heights of power have continued to drag their feet.

The CBCN has splinter groups at the regional or zonal levels. The Onitsha Episcopal conference – comprising of the younger dioceses in the South-East zone – Enugu, Nsukka, Aba, Nnewi, Abakaliki, Awka – decided to take the matter to the grassroots. Early in July this year, the Catholic bishops in the zone met in Aba, Abia state, on the same theme – ways of fostering peace and justice in the zone. This followed the growth of calls for the return of Biafra. Some Igbo youths, under the aegis of IPOB, had been clamoring to opt out because there is no social justice in Nigeria. The Catholic bishops advised the political leaders to de-emphasize coercion as a bargaining chip and invite champions of separatist bodies to the conference table. The advice fell on deaf ears. Unfortunately, a few weeks after that forum, the federal government approved a military exercise known as Operation Python Dance 2 – which allowed armoured tanks to roll into the streets of Umuahia, the Abia state capital. Under the guise of maintaining law and order, some innocent people were killed by the troops. There was lamentation and great mourning in the land as the theme of Peace and Social Justice loomed even larger.

The federal authorities in Nigeria seem not to appreciate the need to talk with the people on the way forward. In Central African Republic, CAR, which shares borders with six other African countries – Chad, Cameroon, People’s Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and Sudan -the fighting and social strife there have become legendary. But the political leaders have gone a step further than Nigeria. Although the most recent agreement, signed there last June, has not stopped the upsurge in violence in the country’s eastern provinces, the benefits of round-table talks have been noticed.

The parleys have served as the spring board that prepared the ground for religious leaders and political activists to declare that peace will not come to the country until the perpetrators of violence are brought to justice. The input of representatives of the various communities helped to fashion out a peace-building strategy which focused on ways of renewing trust between the people and the government. Critics say that there is no indication that the desired end will come any time soon but what is vital is that the first step has been taken.

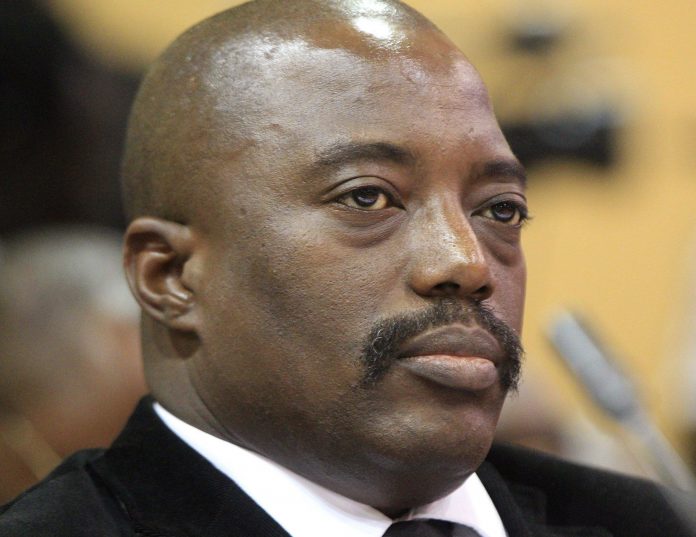

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo DR, the tactics of President Joseph Kabila are well known. He leads a government that lacks genuine legitimacy and has continued to ride rough shod over the feelings of his people. For starters, without being elected, Joseph Kabila stepped into the shoes of his slain father, Laurent, who in turn, had shot his way into office. Apart from shunning all calls on the government to consider ways of bringing all the warring groups to the conference table, cries of marginalization of some ethnic groups have grown louder in the country. Attempts by humanitarian actors and community leaders to point the government in Kinshasa to the direction of peace, tolerance and social justice have continued to be rebuffed by President Kabila and his cohorts. To worsen matters, the President is leaving no stone unturned in his bid to perpetuate himself in office and possibly enthrone himself as president-for-life.

President Kabila occasionally allowed sectional leaders to meet and discuss the implementation of plans for peace and social justice. But it was always like a wild goose chase – nothing came out of such shows because the authorities are not sincere in their mouthed search for peace and reconciliation. The talks would have resulted in a ceasefire agreement between the warring factions and the government. Nevertheless, in one of the forums, it was agreed that the armed groups would be offered political representation and incorporated into the country’s armed forces to usher in a countrywide ceasefire. However, the day after it was signed, there was an upsurge of violence in the western province of Kivu.

Supporters of the central government in Kinshasa, mostly kinsmen of Kabila and his ruling clique, have been accused of neglecting the interests of their compatriots who risked their lives in the concerted efforts to overthrow the tyrant, Mobutu Sese Seko. Over three decades since that episode, the perpetrators of heinous crimes on the orders of the erstwhile dictator have not been brought to justice.

The case of Kenya, where two elephants have been fighting, is unique. But the African proverb makes it clear that in such a scenario, it is the grass, in this case, the common people, that will suffer. The incumbent president, Uhuru Kenyatta, and the main opposition leader, Raila Odinga, are scions of notable political icons in the land. They continue to be locking horns in the contest for transient political power. They are billed to face voters again at the end of this month to decide who will be Kenya’s next president. While President Kenyatta defines peace as a sine qua non for national cohesion and development, his rival, Raila Odinga, defines social justice as the essential platform for peace. What their duel has succeeded in doing is to create fear and mistrust in the political domain and in the interactions among the citizenry.

Africans need to understudy how the advanced democracies of the world attained their current developed levels. One class of thought says the starting point is to get the developing nations to minimize corruption and enunciate something like a Bill of Rights in their territories. Governments must respect the rights listed in such statutes. Luckily, the United Nations is there to help and to blow the whistle whenever the rights of an individual, community or ethnic group are abridged. There is constant need to sensitize government leaders about the essence of peace, social justice and tolerance.

There is no doubt that a great deal of progress has been made in many countries in building a post-conflict society. What remains, however, is to address the actual and perceived lapses, the fears, and suspicions. According to the popular reggae musician, a hungry man is an angry man. The opportunities and resources available in the public domain in any given society should be made to go round. They should not be coveted by the ruling class or a tiny minority, for whatever reason. In order to promote peace there has to be a functional justice system. Peace and social justice go hand in hand. Each one needs the other to thrive. This may be clear but it is obviously not as simple as it sounds.